What Decades of Alcohol Research Got Wrong - and What It Means for Your Health

What counts as ‘safe’ drinking might not be safe at all

“A little alcohol is good for us.” You’ve heard that, right?

We’re told it’s especially true of red wine - full of those heart-healthy, life-extending polyphenols. That’s worth a toast with a glass of Cabernet Sauvignon.

I’ve never thought too hard about it. I drink modestly - a small glass of wine with dinner. It wasn’t always so restrained. At medical school, alcohol was practically a rite of passage, especially for the guys.

But that didn’t survive the onslaught of being a junior doctor. There wasn’t time to sleep, let alone head down to the pub.

Still, the idea that red wine might be good for us raises some awkward questions:

What about white wine?

Or spirits?

How much is “a little,” and how much is too much?

Are you drinking the ‘right amount’?

Are you sure there is a right amount?

Let’s root around in the science and see what we find.

Where the ‘alcohol is healthy’ idea came from

At medical school, we were taught that a little alcohol helps prevent coronary heart disease.

It wasn’t just an old wives’ tale - it was science.

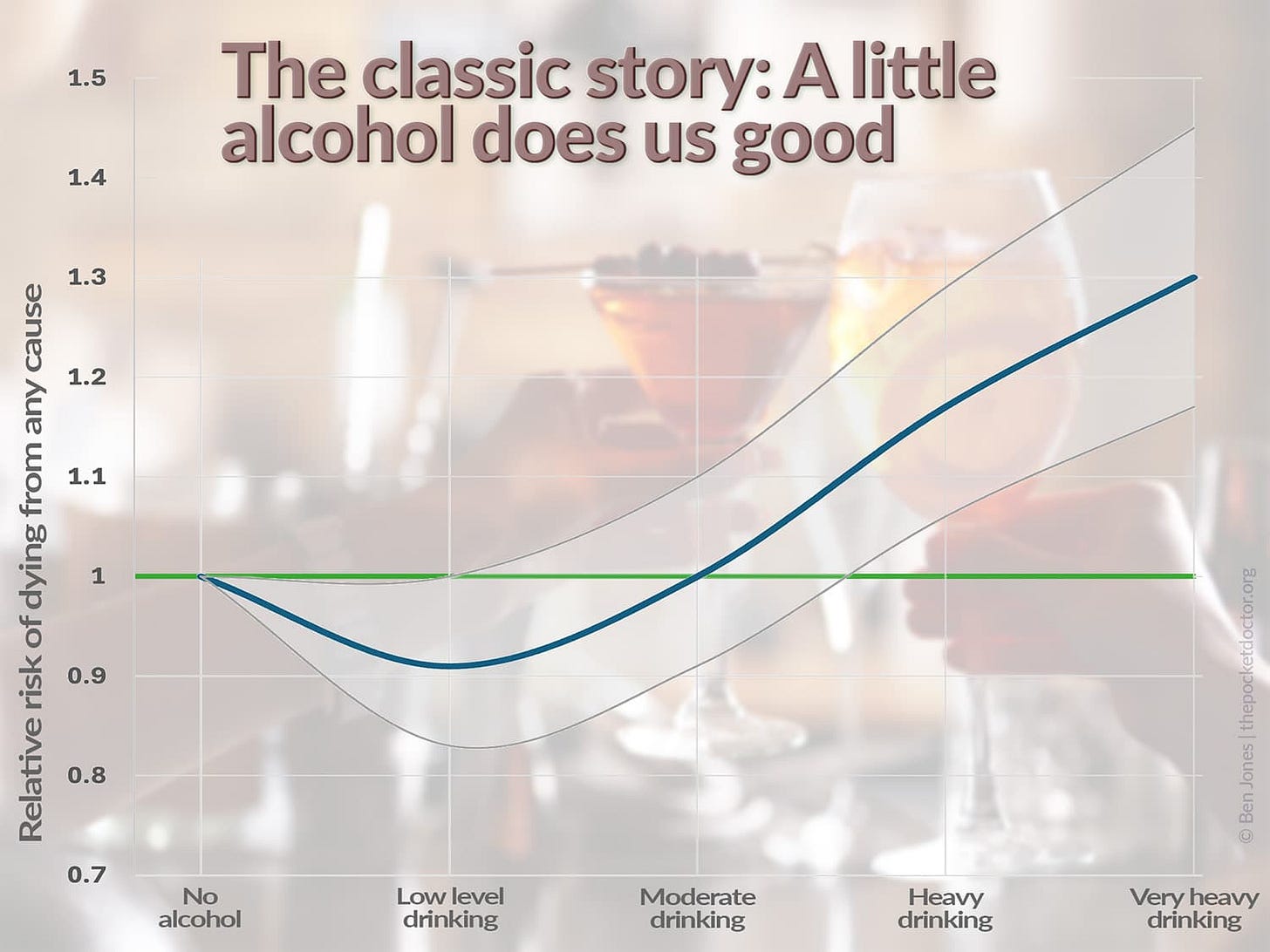

The evidence came from graphs like this one:

The graph shows a classic U-shaped curve: those drinking a little alcohol have the lowest risk of dying from any cause. Moderate drinkers lose that benefit. Heavy drinkers fare the worst of all.

It looks like the perfect excuse to raise a (small) glass, right?

This graph has reassured drinkers - and their doctors (often the same people) - for decades.

But what if I were to tell you it’s based on a fundamental mistake?

The big alcohol myth

Here’s where we went wrong.

Researchers have always compared drinkers to non-drinkers. If alcohol might help or harm, that seems logical, right?

But people don’t avoid alcohol for just one reason. Non-drinkers fall into two very different groups:

1️⃣ Lifelong non-drinkers

People who choose not to drink - for religious, cultural, or personal reasons. They’ve never been drinkers.

2️⃣ Former drinkers (aka the “sick quitters”)

This group includes people who:

Used to drink heavily but stopped, often due to health issues.

Developed a serious illness, then gave up alcohol.

Take medications that don’t mix with drinking.

Got older and quietly phased it out.

See the problem?

Non-drinkers aren’t all healthy. In fact, many former drinkers stopped because they were already unwell.

By lumping them in with lifelong abstainers, researchers unintentionally stacked the non-drinker group with people who already had higher health risks. That distorted the results, making light drinkers look healthier than they really were.

It seems obvious once you see it, but it took the scientific community a long time to catch on.

When researchers re-analysed the data and looked only at lifelong abstainers, the story changed dramatically.

Let’s see what the graph really looks like when you compare drinkers with lifelong abstainers:

The message is brutally clear: the more alcohol you drink, the higher your risk of dying early.

There’s no U-shape. No protective effect from drinking lightly.

On average:

10g of alcohol per day (about one small glass of wine) = average risk of dying prematurely

More than 10g = higher risk

Less than 10g = reduced risk.

It’s sobering, isn’t it? The healthiest amount of alcohol to drink is… none at all.

And look, I realise this isn’t helping my reputation as the killjoy in your inbox - but may I remind you: I brought you nuts. That’s a 17% risk reduction in premature death free with a tasty snack, right there!

Rethinking the 14 units rule

You probably know your country's alcohol guidelines. Here in the UK, the recommended limit is 14 units per week - roughly two small glasses of wine or beers per day.

That sounds reasonable… until you check it against the graph.

Drinking 33g of alcohol per day (those two small glasses of wine or beers) increases your risk of dying early by around 70%

One regular glass of wine or small beer per day (~16–17g of alcohol) raises the risk by 20%

Half a bottle of wine daily? Your risk of premature death doubles.

So while 14 units might be within the guidelines, that doesn’t mean it’s safe.

What's your number?

If you drink, you’re probably wondering: where do I fall on this risk curve?

Let’s find out.

Here’s a quick-reference cheat sheet showing the alcohol content of common drinks:

How to use it:

If you drink the same amount daily, just use that number.

If your drinking varies, add up your weekly intake and divide by seven to get your daily average.

Now you’ve got your grams per day - scroll back to the second graph and find your place on the curve.

Let’s say you drink two large glasses of wine with dinner. That’s 2 x 26g = 52g of alcohol a day.

Trace 52 along the bottom axis of the graph. Now move up to the curve.

You’ll see that your risk of dying prematurely is around 2.4 times higher than if you didn’t drink at all.

That might sound alarming, so let’s put it in context.

A typical 55-year-old American woman has a 0.51% chance of dying in the next year (according to CDC figures) - that’s about 1 in 200)

Drink two large glasses of wine daily, and that risk rises to 1.02% - 1 in 98

A typical 70-year-old American man has a 2.02% annual risk (around 1 in 50)

Add those two glasses of wine each day, and it climbs to 4.03% - 1 in 25

And that’s just over one year. Now let’s look at the five-year risk:

For the 55-year-old woman, her risk rises from 1 in 33 to 1 in 14

For the 70-year-old man, it jumps from 1 in 8 to 1 in 4

We all think about risk differently. But now you’ve seen the numbers - how do you feel about your odds?

Has it changed how you see your nightly glass of wine?

The red wine exception?

We all like to think we’re a bit special - that harmful habits don’t apply to us.

“I drive carefully, so I don’t need to wear a seatbelt.”

So what if you’re a red wine drinker?

Can you confidently pour another glass, safe in the knowledge that red wine is part of the famously healthy Mediterranean diet?

Red wine advocates often point to its high levels of polyphenols - plant compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

But not so fast.

Alcohol-free wine contains all the same polyphenols - without the alcohol. So you can get the benefits without the risk.

Even red wine with the polyphenols removed still raises blood antioxidant levels, suggesting something else may be going on.

Besides, if polyphenols are the goal, why not just eat grapes?

Before you reach for the corkscrew, consider this:

Wine drinkers tend to live healthier lives overall. In many studies, they’re younger, smoke less, exercise more, and have higher levels of education.

Their lower health risks are thought to reflect lifestyle, not the alcohol.

More wine still means more risk. Even among wine drinkers, cirrhosis risk increases in direct proportion to alcohol intake.

Bottom line: If you’re drinking red wine for your health, you’d be better off with grapes or a good alcohol-free bottle.

What does it all mean?

So, what am I saying - should we all stop drinking?

Look, I enjoy a glass of wine. It can lift a ho-hum dinner into something a bit more celebratory. And I very much doubt I’ve had my last glass.

But we do need to retire the idea that a little alcohol is good for our health.

It isn’t.

If you’ve ever done a parachute jump, you’ll know the feeling - thrilling, exhilarating, and more than a little terrifying.

Before you get on the plane, they make you sign a waiver. You have to acknowledge that while this might be fun, you understand the risks.

That’s the mindset we need to bring to alcohol.

So - how about you?

Now that you’ve seen the real numbers:

Are you comfortable with your current drinking habits?

Or do those numbers push you out of your comfort zone?

Because if they do, here’s the good news:

You’re not giving something up. You’re gaining control over a health risk you hadn’t fully seen before.

HEALTH TWEAK OF THE WEEK

Reframe alcohol as a risk you manage, not a health boost.

That daily glass of wine isn’t helping you live longer. In fact, it's probably nudging your risk of an earlier death in the wrong direction.

This week’s tweak: Make your alcohol intake a conscious choice, not a casual habit.

Here’s how to do that:

🧮 Calculate your average daily intake using the cheat sheet above. How many grams per day do you drink?

📈 Locate yourself on the graph. Are you below 10g per day? Above 20g? Further to the right?

🧠 Decide: Are you comfortable with the risk that comes with that level of drinking?

If not, try this:

Swap one daily drink for a non-alcoholic version (there are brilliant reds and beers now).

Reserve alcohol for social or celebratory occasions, not default dinners.

Pair alcohol with food, never on an empty stomach.

Don’t drink alone: psychologically, it matters.

You’re not “cutting back” - you’re upgrading your drinking habits.

You're becoming the kind of person who drinks with intention, not out of routine.

This is why One Health Tweak a Week exists.

Not to chase fads, but to bring you quiet, evidence-based shifts that genuinely move the needle.

One tweak that could halve your risk of dying in the next five years.

That’s huge. That’s worth five minutes of reading on a Saturday, right?

🎧 Prefer to listen?

🎙️ This week’s episode of the One Health Tweak a Week podcast takes a closer look at alcohol:

Why that graph showing benefits from light drinking isn’t what it seems

How ‘sick quitters’ distorted decades of research

What the data really says about red wine, polyphenols, and the Mediterranean myth.

Plus: how to reframe alcohol as a conscious choice, not a health supplement.

👉 Tune in now - it’s free!

(Psst: these episodes are free for now—but won’t be forever. If you’ve been finding value here, consider upgrading to stay in the loop and ahead of the curve.)

👉 What’s next?

💬 Do you think about alcohol as a health decision, or a habit? Has this week’s piece changed how you see your evening glass of wine? Hit reply - I'd love to hear where you stand.

📢 Know someone who still thinks red wine is good for their heart? Forward this to them. Science has moved on.

❓ Got a myth, health trend or “common sense” rule you want stress-tested? Send it my way. It might feature in an upcoming issue.

🔒 Want to help keep this newsletter thriving? Upgrade to a paid subscription for bonus content, Q&As, community chats and the warm glow of supporting real, evidence-based health advice.

Until next Saturday - stay curious, stay well, and stay kind to your future self.

– Ben

I’m asking this in good faith (in case that doesn’t come through in text!), but how large was the study, and how diverse was the population? And how (if at all) does this account for genetics? I come from a long line of alcohol abusers who lived well in to their 90’s, along with everyone else on the family. I’ve read a lot about how the consensus now is that any drinking= dangerous, but these anecdotal non-examples from my life cause me to wonder. (For reference, these family members are white/wealthy, do these studies account for other risk factors like race and poverty?)

Excellent Article. Thank You for submitting and putting the facts out there. The oncology professionals have been very much in agreement with your research and conclusions. They put alcohol in the same group as tobacco and asbestos in terms of carcinogens. Pretty eye opening and scary. Thank You. Keep up the great work you do....